Pension systems around the world are often victims of collusive predation of governments and big banks. Australian superannuation which ranks among the top pension systems, is doing its best to emulate worse ones by frequent reforms. In many countries, private savings have been borrowed and spent by governments in counter-productive Keynesian stimulus or siphoned off to the pockets of the elite in neoclassical financialization and globalization, justified by unscientific economic pluralism.

Efficiency and competition (often confusing buzz words) of economic rationalism have been the neoclassical principles guiding government policy in Australian superannuation which has become “a political football” in reality. Required by politicians to come up with more ideas for reform, David Murray, a past CEO of Australia’s biggest bank, has “jumped the shark” in the 2014 Financial System Inquiry. He recommended change to the default fund system soon after the new MySuper default system was implemented in 2013.

Millions of workers have been unwitting beneficiaries of a default fund system which, by historical accident, is run mainly by the Industry sector. Industry funds are based on the mutual concept of profit for members rather than on the market concept of profit for shareholders of Retail funds. The fact that the default funds have done well for members has been ignored by policy makers and instead, they are assumed to be uncompetitive, because they are not driven by the motive of corporate profits. The corporate-greed lessons of the global financial crisis when markets failed, have not been understood or learned by governments.

A change of leadership of the Liberal government in September 2015 provided the opportunity for Scott Morrison, the new Treasurer, hastily to call an inquiry to change the default fund system. The 2014 Murray recommendation was predicated on an assessment by 2020 of the ineffectiveness of the new MySuper default system. Without bothering with such an assessment, Scott Morrison has “jumped the gun” in February 2016, tasking the Productivity Commission (PC) to develop alternative default models.

This PC inquiry provides a case study of how unscientific economic theories of markets are used mindlessly by politicians to advance their own interests by ignoring facts. The following submission to the PC inquiry provides further details.

Comments on Productivity Commission Draft Report on Alternative Default Models

The Australian Government requested the Productivity Commission (PC) to conduct an inquiry to develop alternative default models in Australian superannuation. The idea of alternative default models was first raised in 2014 by a recommendation in the final report of the Financial System Inquiry (FSI).

Financial System Inquiry

Recommendation 10 of the final report of the FSI (Murray et al, 2014, p. xxiii) states:

Improving efficiency during accumulation

Introduce a formal competitive process to allocate new default fund members to MySuper products; unless a review by 2020 concludes that the Stronger Super reforms have been effective in significantly improving competition and efficiency in the superannuation system.

In this quote, emphasis has been added to show that the FSI saw no hurry in introducing new processes for allocating default fund members to MySuper products. The impact of MySuper products and the Stronger Super reforms would have to be assessed as being ineffective by 2020 before new reforms are to be considered.

The FSI (Murray et al, 2014, p.55) provided the following reason for making this recommendation (emphasis added):

The superannuation system is not operationally efficient due to a lack of strong price-based competition. As a result, the benefits of scale are not being fully realised. Although it is too early to assess the effectiveness of the Stronger Super reforms, the Inquiry has some reservations about whether MySuper will be effective in driving greater competition in the default superannuation market.

The FSI implicitly attributed the lack of strong price-based competition and the operational efficiency of the whole superannuation system to the default funds. Otherwise, why was this reason given for singling out default funds for attention? In fact, default funds are one of the best performing segment (see below), but their assets represent less than one quarter of the whole superannuation system.

In neglecting to address competition and efficiency on the other three quarters of the superannuation system and focusing only on default funds, the FSI seems to be running out of useful reform ideas, thus “jumping the shark”. We suggest that

This FSI recommendation should be rejected by the Australian Government based on false assumptions and inadequate evidence that default funds are mainly responsible for the inefficiency of the Australian superannuation system.

Furthermore, in recommending improvements for default funds, FSI was assuming that the recently implemented Stronger Super and MySuper reforms will be ineffective, according to its own “reservations” or guess work, but based only on insufficient facts or supporting evidence. The FSI was wise enough to realize that further evidence needs to be collected by 2020 before consideration should be given to further reforms of default funds.

The judgement by FSI that the Stronger Super and MySuper reforms will be ineffective in improving competitiveness and efficiency of default funds is therefore premature and unconvincing. Indeed, it was not until 2014 that the first MySuper data were published by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), providing information on the new reforms. Even accepting that the system of default funds could be improved, more objective analysis based on empirical evidence is needed to decide what needs to be improved. We suggest that

The necessity for further reforms to default funds needs to be considered only after 2020 when the impact of recent reforms of Stronger Super and MySuper has been properly assessed.

Productivity Commission Inquiry

In February 2016, the Treasurer, Scott Morrison, who hastily requested the current inquiry, suggesting in the Productivity Commission Draft Report (Harris et al, 2017, p. iv) that

The Financial System Inquiry noted that fees have not fallen by as much as would be expected given the substantial increase in the scale of the superannuation system, a major reason for this being the absence of consumer-driven competition, particularly in the default fund market.

This statement is factually wrong because

- The default fund market is only a small part (less than a quarter) of the Australian superannuation system and therefore cannot be a major reason for the inefficiency of the whole system.

- In any case, the default fund market is the most efficient part, compared to the other parts of the system. On average, data show many MySuper default funds have large scales and low fees, easily surpassing the performance of most non-default funds.

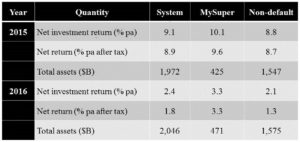

Official data published on 1 February 2017 by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA, 2017a, 2017b) are used to compare asset weighted, Net investment returns (before super tax) and Net returns (after super tax) for 2015 and 2016, the only years for which MySuper product returns can be calculated accurately. The performances of the whole superannuation system, MySuper and non-default funds are compared in the table below, where the performances of non-default funds have been deduced from the measured results of the whole system and MySuper performances.

- In 2016, the MySuper default fund market was only 23 percent by total assets of the whole superannuation system. It cannot be the major reason for the inefficiency of whole system.

- The MySuper default fund market has performed consistently and significantly better than the non-default fund market. Default funds generally have greater scale and lower fees than non-default funds.

The MySuper default funds appear likely to the best segment of the Australian superannuation system and reforming them are unnecessary and premature. Rather than reforming the default fund market, the Government should be reforming the non-default fund market, where the greatest inefficiencies are likely to be found.

In hastily calling the current PC inquiry so soon after a change of government in September 2015, the Australian Treasury has provided no additional evidence for why the FSI recommendation on default funds needs to be accelerated ahead of the 2020 assessment. Therefore the current inquiry into default funds by the Productivity Commission (PC) has “jumped the gun” on the 2020 assessment and also “jumped the shark” being based on an unconvincing idea on superannuation reform originating from the FSI (Murray et al, 2014).

PC Draft Report

Starting from a false and wrong-headed premise about default funds, it is difficult therefore for the PC to come up with anything useful in the draft report (DR). The following is only a partial list, in many different respects, of the deficiencies of the DR.

- The report (DR) is remarkably free of hard facts and statistics which would have been inconvenient for the task. In particular, no factual evidence has been provided to show that default funds have high fees, or higher fees than non-default funds.

- The DR has admitted (p. iv) that

MySuper has been a strong step in the right direction but more needs to be done to reduce fees and improve after-fee returns for fund members.

Its “no defaults baseline” approach: “Having no defaults is our preferred, objective baseline for this inquiry”, contradicts its own assessment that “MySuper has been a strong step in the right direction”. Why start from scratch?

- The DR has ignored an enormous amount of research on default options cited in the Super System Review (Cooper et al, 2010) without adequate explanation. The PC did not come up with its own articulated view, based on its own analysis and research, about what is wrong with the current system of default funds.

- The PC does not seem to understand that choice of defaults is essentially an oxymoron. When superannuation members want choice, they do not use defaults. Defaults are bland and homogenous precisely for reasons of comparability and competition which the PC is supposed to encourage rather than to oppose.

- The PC has amassed, for the bulk of the report, a great volume of opinions from submissions; but without its own researched view of the superannuation system, the PC cannot assess whether the opinions it cited have any merit. The list of findings of the DR is merely a list of arbitrarily selected opinions.

- The PC has not analysed the strengths and weaknesses of MySuper, the current default system. Without this understanding, it is not really possible to compare it with alternative default systems. This may explain why “no defaults” is its baseline in the DR.

- No system is perfect. Every system has strengths and weaknesses. The right system has to be compatible with the particular regulations, values and culture of the country. Listing default systems of many countries is not adequate for deciding how the Australian default system should be reformed.

On the evidence of the DR, the PC has added little of substance to our understanding of the Australian superannuation system and the work on alternative default models is not based on a sound foundation.

Conclusion

The current inquiry into alternative default models can be characterized as both “jumping the shark” and “jumping the gun” on superannuation reform. It is not as though Australia has been inactive in reforming superannuation. On the contrary, there have been far too many half-baked and ill-considered reforms, not based on careful, evidence-based research. With some justification, many in the industry and in the media have observed that “superannuation has become a political football”. We conclude that

It is unarguably premature now to justify or to develop sound procedures for selecting alternative default models. The present inquiry should be abandoned as a waste of government resources.

References cited above are given in the original submission.

The Australian government, in last night’s budget, plans to levy a special tax (0.06 percent of their liabilities) on the big banks. This may appear to some people as a contradiction to our claim of “collusive predation” on ordinary citizens. The action only appears to be taxing the big banks – it is not actually.

It is really another tax on consumers for the purpose of raising government revenue, because the tax is basically a 0.06 percent levy on bank deposits (bank liabilities), despite some complexities in determining the precise levy. The banks can simply lower the interest rates on bank deposits by 0.06 percent per annum to pay the levy – easily done. The Government has squeezed the savers again on the slim margins of deposit rates above Reserve Bank cash rate (now 1.5 percent, below 2.1 percent CPI inflation rate).

The reason that this tax on big banks will be passed onto consumers is because as deposit-taking institutions, Australian big banks are an oligopoly with considerable pricing power. Competition in deposit-taking is weak in Australia. In December 2016, from official APRA data, the deposits in all 144 deposit-taking institutions totaled $2.68 trillion, of which the big four banks account for $2.13 trillion, nearly 80 percent.

Effectively, the big banks will cooperate with the Government to collect more tax revenue from ordinary Australians through bank deposits, with most people (including media economists) rejoicing at the apparent anti-bank measure. The big banks are reported by the media to be complaining bitterly, pretending that the tax is a big blow to their profits - what a charade!