The global financial crisis (GFC) has been blamed on the failure of capitalism, with the 2011 Occupy protests declaring, “capitalism isn’t working” (Hussey, 2014). What is capitalism which has failed?

Economists appear reluctant to define explicitly key economic terms such as capitalism. For example, whole books on capitalism (e.g. Marx, 1890; Baumol et al., 2007; Kaletsky, 2010; Piketty, 2014) have been written without giving explicit definitions from the start of their lengthy discourses. One has to guess what they mean. Indeed they call many different ideas “capitalism”, for example, as Kaletsky (2010, p.3) asserts:

…capitalism is not a static set of institutions, but an evolutionary system that reinvents and reinvigorates itself through crises…

By inference, capitalism is then defined by the evolving economic systems of Western countries. This proxy definition is also consistent with that of Piketty (2014) who also views the economic history of Western countries as the economic history of capitalism in his study on the cause of wealth inequality. This association and implicit definition of capitalism create noise, muddled thinking and outright errors. As will be shown below, socialism (to be defined) has been a significant component of Western economies for many decades.

Definitions

As a valid universal concept, the definition of capitalism cannot depend on time and space – it has to be applicable to any time and at any location. Otherwise, no general statement about capitalism can ever validly be made. What has been evolving in Western economies is not the essence of capitalism itself, which must be space-time invariant, but actually changing ways of exploiting the freedom of private property, alternative political agendas and varying levels of adoption of socialist policies. Capitalism should not be defined by the changing economic systems of Western countries – instead, a scientific definition is needed and is given here.

Capitalism refers to an economic system which allows individuals privately to own and use capital. Capital is the means of production including resources, property, technology, knowledge, goods and services which are useful for production. Capital in macroeconomic data is often referred to as “fixed capital”. In the twenty-first century, all countries are capitalist to some degree, because most individuals can own private capital. But no country is purely capitalist, because some private properties are usually confiscated by the state, to a greater or lesser extent, through taxation and inflation.

Socialism is an economic system where the state or the society as a whole owns and controls capital and its uses. Since the state acquires most of its capital from its citizens directly or indirectly through taxation and other means, socialism involves coercive acquisition of individual capital and is a partial denial of private property – it is a contradiction of capitalism. Hence socialism is opposite to capitalism. Note that state ownership of capital is different from collective ownership, because the latter allows the individual rights to shared ownership of collective capital, but the former denies any individual rights to the property of the state.

Note also that these definitions of capitalism and socialism are purely economic and universal, unencumbered by ideas from politics or finance. Clear definitions do not restrict, but help, the development of other ideas. When economists discuss capitalism, they usually by association confound the essence of capitalism with all sorts of other extraneous ideas from management, finance and politics such as competition, markets, democracy, etc.

For example, Baumol et al. (2007) introduce four types of capitalism: state-guided capitalism, oligarchic capitalism, big-firm capitalism and entrepreneurial capitalism. The qualifying ideas are not essential or universal attributes, because they are merely current ways of exploiting the freedom of private property and their conceptual addition may involve logical contradictions. For example, does state-guided capitalism imply restrictions on the private use of capital? By identifying capitalism with changing Western economies, as done by Kaletsky (2010) and Piketty (2014), capitalism becomes a mixed bag of shifting ideas even including socialism, its antithesis as defined here.

Given our definitions, the following passage (Piketty, 2014, p.99) makes little sense:

Throughout the Trente Glorieuses, during which the country was rebuilt and economic growth was strong (stronger that at any other time in the nation’s history), France had a mixed economy, in a sense a capitalism without capitalists, or at any rate a state capitalism in which private owners no longer controlled the largest firms.

By our definition, the key ideas in capitalism are private and capital. State capital has legitimate meaning as capital owned by the state. But state capitalism is an oxymoron. What we would probably say instead is that, during the thirty glorious years after the War, France was essentially a socialist country. If this is the case, then the period should not be included in the history of French capitalism.

Indeed, all countries are socialist to some degree where the state expropriates capital from its citizens directly or indirectly through taxation and other means to use according to its priorities. The main uses of state capital are public administration, law enforcement, public infrastructure, welfare and warfare. Capitalism requires at least one function of the state which is to enforce laws protecting individual property rights. Hence capitalism cannot be entirely free of the state or some other protective agency.

A priori, capitalism or socialism is neither good nor bad in itself. It is only better or worse, in practice, relative to certain economic objectives. Economic objectives evolve in time or space (i.e. geography). From the start of any science inquiry, it is inappropriate to assume that capitalism or socialism is either good or bad. Such a dichotomy leads to adoption of left or right prejudices which compromise the integrity of any scientific inquiry and plague virtually all economic theories.

Metric for Capitalism

To be able to decide objectively whether a particular country is more capitalist than socialist and vice versa, we need a metric for capitalism or socialism. Since the government confiscates private property which is usually part of personal income and corporate profits to fund ongoing public expenditure, a metric for socialism can be defined by government total expenditure as a percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) publishes a macroeconomic database which is used in its World Economic Outlook (WEO) reports. The data for 189 countries are lagged generally by a few years. At the time of this writing, the last year of reasonably complete and verified (rather than estimated) data was 2012. Before 2002, the WEO database also has many gaps, particularly for smaller countries. For the purposes of this paper, we select data for the ten year period 2003-2012.

The data used to measure the size of government has the WEO subject code: “GGX_NGDP”, which measures general government total expenditure as a percentage of nominal GDP. Total expenditure consists of total expense and the net acquisition of non-financial assets. Apart from being on an accrual basis, total expenditure differs from the IMF’s own Government Finance Statistics Manual (GFSM) 1986 definition of total expenditure by also taking into account the disposals of non-financial assets. The data suggest that some countries have been funding government expenditure through privatization or the sale of public assets such as public utilities.

Degrees of Capitalism

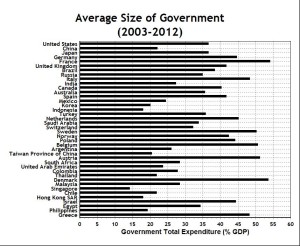

The chart below shows the sizes of government defined as government total expenditure for 40 largest economies averaged over 2003-2012, sorted in descending order of the size of economy.

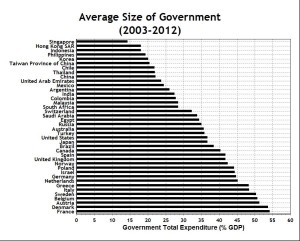

The United States and China account for more than 35 percent of global GDP. The above chart shows that there is apparently no correlation between the size of economy and the size of government. The chart below shows the same data sorted in ascending order of the size of government.

If we were to divide the top 40 countries into two groups of equal numbers, with one group being labelled capitalist and the other group socialist, then Russia and countries above it would be capitalist and Australia and countries below it would be socialist. This division and nomenclature are entirely arbitrary and are created only for convenience of discussion of the current dataset – it may be more precise to say more capitalist rather than simply capitalist in describing countries. Heading the capitalist group are Singapore and Hong Kong SAR, followed by other developing countries. Milton Friedman (1997) considered Hong Kong to be the paragon of natural experiments in free-market capitalism.

On the other hand, the United States, United Kingdom and most countries in Western Europe belong to the socialist group – the exception being Switzerland. It is interesting that, in purely economic terms, China and Russia are more capitalist than US and UK. The GFC originated from the socialist group of countries and they suffered from the most serious recessions, while the capitalist group of countries were less affected (see below). Hence it is difficult to conclude that “capitalism has failed”. It is ironic also that Piketty is a citizen of France which is the most socialist or least capitalist of all major economies. Apparently the largest socialist economy in the world has not solved its own problem of wealth inequality, which Piketty (2014) has blamed on capitalism.

Economic Growth

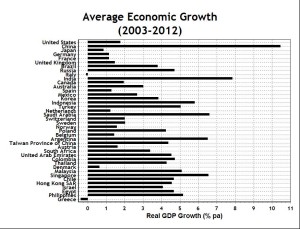

For the economic growth history of the same top 40 countries, the WEO database provides data for annual growth rates of GDP at constant prices with WEO subject code: “NGDP_RPCH”. They are annual percentage changes of constant price GDP year-on-year; the base year is country-specific. Expenditure-based GDP is total final expenditures at purchasers’ prices (including the free-on-board values of net exports of goods and services). The arithmetic averages over a ten-year period are shown in the chart below, in descending order of size of economy.

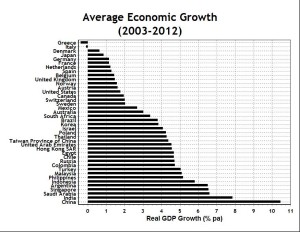

China appears as a statistical outlier, which may cast doubt on the accuracy of its official data. The data show Greece has already had a lost decade by 2012. There is also apparently no correlation between the size of economy and average economic growth. The chart below shows the same data sorted in ascending order of average economic growth.

Again, if we were to divide the same top 40 countries into two groups of equal numbers, with one group being low-growth and the other group being high-growth, then Brazil and countries above it would be low-growth, while Korea and countries below it would be high-growth. Again, this nomenclature is used only for convenience of discussion. It is evident from the above rankings (seen in the charts) that capitalist/socialist and low/high group memberships are correlated.

There are 17 countries in each of the two groups: low-growth socialist and high-growth capitalist. The perfect binary rank correlation between capitalism and growth is marred only by 6 off-diagonal elements in the correlation matrix, being in the high-growth socialist or in the low-growth capitalist groups. The high-growth socialist countries are Israel, Poland and Turkey, while the low-growth capitalist countries are Switzerland, Mexico and South Africa.

Capitalism and Growth

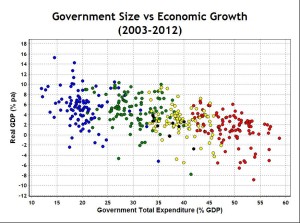

To examine the statistical relationship between capitalism/socialism and economic growth, the annual relationships between government total expenditure and real economic growth for the 40 countries are shown in the chart below, where each dot represents a data pair for Government Total Expenditure (% GDP) and Real GDP Growth (% pa) for one country for one year.

The blue dots represent the bottom quartile of countries in terms of size of government (measured by average government total expenditure), while the green, yellow and red dots represent succeeding quartiles. The black dots represent the US, the largest economy in the world. Evidently, there is substantial volatility in the data from year to year, as the period includes the years around the GFC. Nevertheless, the anti-correlation coefficient at -0.54 is statistically significant, with an R-square of 0.29.

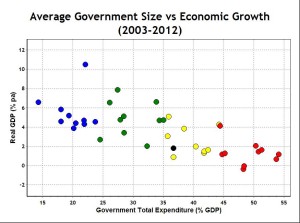

Some of the noise in the data may be removed by taking averages over the ten-year period for each country. The 400 data points then reduce to 40 data points shown in the chart below, where each dot represents a data pair for Government Total Expenditure (% GDP) and Real GDP Growth (% pa) for one country averaged over ten years.

The statistical significance of the relationship has improved, with the anti-correlation coefficient increasing to -0.71 and the R-square increasing to 0.51. Note the order of the dots and their country names are given as in the second chart of this post. Singapore is at the extreme left of the above chart, while Denmark and France are at the extreme right of the chart. The degree of socialism increases monotonically from left to right on the bottom axis.

The regression model for this dataset suggests that for every ten percent increase in the size of government, defined by government total expenditure as a percentage of GDP, the average economic growth rate falls by about 1.5 percent per annum. While this fact is statistically and economically significant, by itself, it is not necessarily an argument against socialism. But the fact that there is a cost should be considered along with all relevant social and economic objectives.

Conclusion

The clear definition of capitalism introduced in this post provides a scientific basis for understanding and interpreting facts. The empirical evidence presented here strongly contradicts the belief that “capitalism has failed” before, during or after the GFC. In fact, the capitalist economies of the emerging markets had to weather the storm created by the major centres of financialization (located in socialist countries) and propagated through capital flows of globalization. It has been capitalism which has provided the flexibility and resilience in the emerging economies to survive the fallout from the GFC.

Except for China, the emerging capitalist economies do not have large governments or central banks which are constantly stimulating their economies, fixing interest rates, increasing money supplies and manipulating financial markets. The emerging capitalist economies also do not have large welfare and pension systems through which savings are transferred and spent by governments on current consumption, creating a mountain of public debt (Sy, 2015c).

Private savings in emerging capitalist economies had to be used to generate real investment returns in economic production to fund future consumption for individuals in retirement. Private debt had to be carefully managed by individuals, because bad private debts cannot be rescued simply by transferring to public debt by governments which have been creating moral hazard through constant meddling in Western countries.

From a scientific point of view, there is no a priori reason, based on sound theory or evidence, to suggest that it is impossible for governments to be beneficial to their economies. By the same token, governments need to accept their economic ignorance and need to observe the consequences of their actions and to stop digging when they find themselves in a Keynesian hole (Sy, 2014).

Capitalism has been good for economic growth. This does not mean governments should privatize natural monopolies such as public utilities, as they have done. The current paradigm of mainstream economics is unscientific and has led to many bad policies based on false theories. There has not yet been a reliable theoretical basis from which governments can manage economies effectively in any systematic or substantive way.

Since the GFC, Western countries have practised extreme socialism by expropriating many trillions from savers and taxpayers and have given it to failed financial institutions, violating the essence of capitalism. Failure to generate economic growth in many countries has come from a lack of capitalism, not because of it. “Capitalism isn’t working” for Western countries may be because there has not been enough of it to promote economic growth.

A slightly extended version of this post is available for free download here.

Entirely relevant and most Appropriate and well written:

by Hugo Salinas Price

http://www.plata.com.mx/Mplata/articulos/articlesFilt.asp?fiidarticulo=270

The fundamental flaw of economics, including mainstream economics and Austrian economics, is that economists don't understand science. Salinas Price wrongly disagnosed the mainstream problem with the inductive method which mainstream economics hardly ever uses.

Like all economics, the mainstream places little weight on facts or empiricism, despite appearances. Mainstream economics is also deductive like Austrian economics - except they start with different assumptions about human behaviour and one school tells its stories with mathematics and statistics, whereas the other with loose verbal reasoning.

The reason that Austrian economics was better in the global financial crisis (or for understanding any crisis) is that its assumptions are more realistic than mainstream economics. Austrian economics assumes that humans can err with e.g. malinvestments, which are impossible in mainstream economics.

No school of economics takes facts or empirical evidence seriously enough. Their stories never change with new evidence and with changes in regulations, institutions, technology etc. Science needs both deduction and induction - it needs constant confrontation with reality to remain relevant.

Most posts on this blog are critical of Keynesian economics because it is the dominant theory affecting contemporary economic policy. This does not imply approval of its opposites: neoclassical or Austrian economics. Hence I should take this opportunity to make a few more comments on the Austrian opposite camp.

Salinas Price says the scientific method is controlled experimentation (defined by Bacon). If this is a correct definition of science then astronomy and astrophysics cannot be sciences because there has never been controlled experiments in those subjects, only observations. Salinas Price does not understand what is science.

Empiricism and any inductive hypothesis in economics have to occur via observations, like astronomy, not through controlled experiments (which are generally impossible due to too many variables). This post has an inductive hypothesis: capitalism is associated with higher economic growth than socialism. It is an empirical observation without controlled experimentation.

Salinas Price then attributes recent central bank policies of quantitative easing, zero or negative interest rate policies to "experimenting upon mankind", implying that authorities are pursuing his idea of science (defined by inductive method and controlled experiments). This is a far-fetched assertion because the authorities are not trying to discover economic truths - they are trying to control or direct their economies based on flawed economic theories.

Austrian economists like Salinas Price attempt to identify the unscientific policies and actions of central banks and mainstream economists today with science and in turn justify their own disdain for science. The Austrian method based on the logic of human action (or praxeology) is purely deductive. Purely deductive methods are just as prone to errors, as there are many known logical fallacies and many known material fallacies in e.g. Aristotelian physics. Deductions do not necessarily lead to truths.

According to our definition of science, Austrian economics is unscientific (yet some Austrians claim praxeology is a science). Austrian economics, like other economics, is prone to Aristotelian fallacies.

"One has to guess what they mean. Indeed they call many different ideas “capitalism”, for example, as Kaletsky (2010, p.3) asserts:

Comments:

'evolutionary' - Yes, due to the fact that humanity, or that entity which practices capitalism, is in a constant state of evolution itself, at all times; not animately, but cognitively and emotionally. And, this evolution is not a linear, but, a differentiation process.

'system' - Not so. Merely human behaviours in natural interaction, where property ownership is intrinsic to the individual human.

Perhaps the above could be better stated as: "…capitalism is not a static set of institutions, but the natural expression and 'right action' of animated mans' evolution as humanity", whereas "Economics" is a system, which is dedicated to Recursively Scamming this 'capitalism'. Man does not Manage his own affairs, as he Kneels, before Power.

I agree that economics and economics education are parts of the system dedicated to "recursive scamming" by brain-washing and lobotomizing economists so that they serve their masters obediently. I test regularly to see if the system has evolved from the dark ages by submitting research papers to journals such Real World Economic Review (RWER) to see whether there is any receptivity to "new economic thinking".

Not surprisingly there has been little evidence of that or of changes to the same self-serving behaviour as described by public choice theory - economics journals are merely vehicles to advance the careers and the schools of those who control them. The editor of RWER held my submitted manuscript for over two months without sending it out to a referee. It was only after I reminded him that he made a lame excuse (thought the manuscript was not a submission) before sending it out.

The low standard of academic review received is something to expose and hopefully fix. The manuscript sent to RWER was "Economic Policy of Debt and Destruction". The editor informed in an email that "on the basis of the review pasted below we are rejecting your paper for publication in RWER". The reviewer's comments (and my remarks) are as follows:

The paper is not about "arguments" or "claims" or "to present a case". The paper is about presenting empirical evidence testing fundamental claims of Keynesian economics.

The paper is not about "consumption-based model", but about facts and data on US consumption and its empirical relation to debt and economic growth. There is no issue with what growth is, because it has been defined standardly as the growth of real GDP.

The passing remark in the paper about digging holes has not a hint about "assuming aggregate demand can be increased without constraint..." The reviewer made up something of his own and criticized it as though it was part of the paper.

Again, these theoretical issues: constraints, aggregate supply, role of labour, etc. are not raised in the paper. The reviewer made up his own issues to criticize.

Again, the paper avoids all theoretical questions about money, debt, etc. It merely observed the growth of debt as a fact and relate this empirically to other economic variables such as consumption and economic growth. The reviewer's comments are irrelevant.

Investment in the paper is defined by macroeconomic data of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. No doubt the measured investment includes good and bad investments. But how much is good or bad is irrelevant to the empirical analysis of macroeconomics presented in the paper. The sort of waffle the reviewer indulges in would not help to advance economic knowledge.

What has this comment got to do with the paper?

In summary, the reviewer has not read the paper well enough to understand that it is not trying make a case for any theoretical claim. The paper is an empirical analysis of official data, on which the reviewer made not a single comment. The paper is not about proposing theory as in most economic papers. The paper presents the latest empirical evidence to show that

1. Economic stimuli over decades have successfully increased consumption financed through debt growth.

2. But increased consumption has led to decreased, not increased, economic growth, contrary to predictions of Keynesian theories.

The paper is testing theory and not proposing theory. The editor of RWER could not have made even the most cursory check on the quality of the reviewer's report. This is another anecdotal example of how useless many academics are. I once told a colleague that 95 percent of economic research is useless - he disagreed and said at least 99 percent is useless. Economists generally do not know the right way to write research papers in economics - imitating academic papers in philosophy or physics is not appropriate.

In response to your: Real World Economic Review (RWER)

No surprise here at all. American Academics are on record in killing off work by those that would challenge the Theories of the Establishment in many fields especially archaeology. Don't think for a moment that this is limited to the Americans, as it isn't.

Power cults devolve the cognitive abilities and independence and deprive them of all morals, ethics and values in the qualitative sense. Lowest Common Denominator (LCD) defines this debaucherous state of Being. Waste of time really, as the Economics Cult rules Supreme, as it sits to the Right of the Banking System.

Orthodox economists make no bones about defending their privileged mainstream position - and one does not expect them to be open-minded and receptive to new ideas. By contrast, heterodox economists are hypocritical and while they pretend to be receptive to non-mainstream "new economic thinking", they are actually closet Keynesians (or post-Keynesians).

No Austrian or anti-Keynesian facts or views are allowed to appear in heterodox literature (e.g. RWER) - it would be blasphemy to their religion. Heterodox economists should be more honest and call themselves socialist economists, who are only a small subset of heterodoxy outside mainstream economics.

Heterodox economists are like the pigs in George Orwell's "Animal Farm". If the heterodox pigs ever displace the orthodox men, the pigs would behave exactly like the men they displace - there will be no difference. The last sentence of the famous novella sums this up:

It is self-evident that so-called heterodox economics is riddled with political agendas and preconceptions which cannot possibly lead to useful development of economic knowledge. Heterodox economics is a cuckoo or an imposter, preventing, displacing and pushing out genuinely new ideas.

Imagine a court of law where factual evidence is suppressed to bring about a perversion of the truth. The RWER does the same thing by suppression the empirical evidence I presented on Keynesian economics.